Martin Luther King Jr. in Montreat

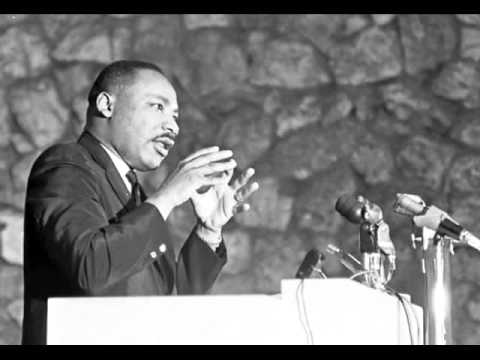

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s address to the 1965 Christian Action Conference in Montreat is one of the most celebrated events in the Montreat’s history, serving as a focal point in that era’s conversations on race relations in the church and in American life. Dr. King’s visit to the Anderson Auditorium stage is often cited with honor and pride and its importance remains a focus of conversation, speculation, and questions to this day.

Background

The Mountain Retreat Association (MRA) was the convening space for the Southern Presbyterian Church (PCUS), one of two main Presbyterian denominations in the United States. In June of 1954, the denomination's General Assembly met at Montreat and recommended that churches and other affiliated organizations end practices of segregation. The proposal, called "A Statement to Southern Christians," condemned segregation as theologically flawed.[1] The action of the General Assembly drew both support and resistance from congregations throughout the denomination and in the Montreat community, mirroring the conflicted sentiments in American society at the time. These divisions persisted over the ensuing decade as the MRA struggled with its own policies regarding segregation.

Under a mandate from the 1964 General Assembly, the PCUS. Board of Christian Education’s Division of Christian Action organized the Christian Action Conference, to be held the following year in Montreat. The conference – with its topic, “The Church and Civil Rights,” – aimed broadly to provide opportunities for members of the church to connect with individuals who had been active in the Civil Rights Movement and to evaluate what role the Church should assume. Board Secretary Malcolm P. Calhoun invited Dr. King to make the keynote address.

Reaction to the Invitation

Word of Calhoun’s invitation swept through the Presbyterian community in the south and nationally. The PCUS staff received communications expressing support and opposition in the forms of letters, phone calls, and telegrams from clergy and lay members. Contemporaneous news reports declared that King’s scheduled speech had caused considerable controversy and opposition, as well as communications commending the board for its action.[2] At one point, there was a call to withdraw the invitation to Dr. King, but the PCUS General Assembly voted 311 to 120 to affirm the invitation.

In the days preceding the scheduled conference, the nation’s attention was captured by the Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles, and concern about King’s visit grew among local residents and law enforcement. Days before his planned arrival, an article in The Charlotte Observer entitled “Don’t Visit N.C., King Told,” reported that Buncombe County officials "felt it would be better if Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. did not visit a church meeting at Montreat," stating there was no need for "outside agitators." Solicitor Robert S. Swain of Buncombe County stated that "there would be no demonstrations against the King visit” and that “there was always an element in a community that could cause trouble.”[3] The Observer also reported that “anti-King" literature was distributed by "a lot of people who were unknown … a rough looking group."

King, who was originally slated to be the opening address of the conferences, was engaged in meetings with L.A. community members, so the schedule shifted, and Rev. Dr. Billy Graham opened the conference. The Asheville Citizen, which had only covered King’s impending visit on page 18 the day before, placed news of the delay of his talk on the front page with the reason for his cancellation – “He is visiting Los Angeles.” They also remarked about Dr. Graham's address, "Although he didn't name any individual, it could be inferred that he was referring to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. [when he said,] 'Any religious leader can express his personal views ... however, President Johnson and Congress are perfectly capable of handling American foreign affairs,'" referring to King's criticisms of the Vietnam War. [4]

Other conference speakers included: other prominent leaders, among them author and activist James McBride Dabbs, and Gayraud Wilmore, a Black Presbyterian minister, ethicist, historian, educator, and theologian, and executive director of the Commission on Religion and Race established by the UPCUSA, the nation’s largest Presbyterian denomination at that time.

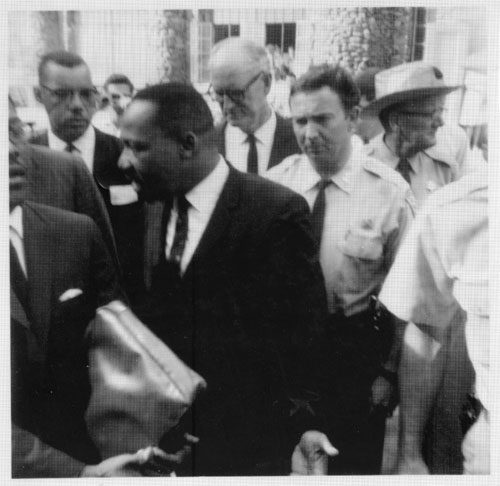

King finally arrived in Asheville on August 21, 1965, and traveled by police escort to Montreat to find it heavily guarded by sheriff’s deputies and state troopers. Henry P. Clay, the county sheriff, reported receiving reports "that certain outside violent hate groups ha(d) planned demonstrations and law-breaking acts at this gathering," but declined to name the groups. "We’ll screen everyone coming in," he said, "and we’ll search autos and individuals for guns if necessary." [5]

King spoke to a packed Anderson Auditorium for nearly an hour and held a question/answer session before greeting the crowd. He did not provide "a blueprint for the PCUS to follow in dealing with the civil rights movement." Instead, his address, titled "The Church on the Frontier of Racial Tension," lamented that future historians will find that “the Christian church in the South was the last bastion of segregated power," and urged churches to "move beyond social reform to help create changes in the hearts and minds of people so they could accept individuals without prejudice."[6]

King left Montreat shortly following and was transported to the Asheville airport and on to his next destination later that day.

Impact

"There were a lot of people who left the church that night, who were not the same people when they left."

In the years since, that day’s events have continued to mark the timeline of Montreat's history in the minds of many. Memories of division and controversy have receded into history as people recall the excitement and pride of the presence of Dr. King in Montreat. Some name the visit as a catalyst in the conference center’s struggle to acknowledge and confront a history that includes racism and segregation, perhaps unfairly discounting such efforts prior to 1965, or perhaps more egregiously suggesting that such work was completed long ago. The event was indeed a historic milestone in the continuing struggle to seek the equity among all people that our theology requires.

Fifty years later, in commemoration of this event, Montreat Conference Center hosted a three-day event entitled "Dr. King's Unfinished Agenda: A Teach-In for Rededicating Ourselves to the Dream" featuring keynoters and activists to recognize this event in its history and to also highlight areas where the conference center and the church have not lived up to the agenda set by Dr. King.

Frequently Asked Questions

Sources

- ^“Ninety-Fourth General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States.” In Minutes of the Ninety-Fourth General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States. Richmond, VA: Presbyterian Book Stores, 1954. https://pcahistory.org/topical/race/PCUS_1954_Segregation_Report.pdf.

- ^The Asheville Citizen. “King’s Montreat Talk Already Stirs Unrest.” August 6, 1965. https://citizen-times.newspapers.com/image/199795353.

- ^The Charlotte Observer. “Don’t Visit N.C., Dr. King Told.” August 17, 1965. https://charlotteobserver.newspapers.com/image/620327228.

- ^The Asheville Citizen. “Evangelist Sees World on Fire.” August 16, 1965. https://citizen-times.newspapers.com/image/199838121.

- ^The Daily Times-News. “For Martin Luther King’s Visit Church Meeting Guarded.” August 21, 1965. https://newscomnc.newspapers.com/image/52982185/.

- ^ Alvis, Joel L. Jr. "Religion and Race: Southern Presbyterians, 1946 to 1983." Print. Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States of America: University Alabama Press, 1994.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Documents on Martin Luther King in Western North Carolina, 1963-1965."

- Alvis, Joel L. Jr. “The Montreat Conference Center and Presbyterian Social Policy.” American Presbyterians 74, no. 2 (1996): 131-39.

- Marshall, Mary-Ruth. “Handling Dynamite: Young People, Race, and Montreat.” American Presbyterians 74, no. 2 (1996): 141–48.

- Davis, Calvin Grier. Montreat: A Retreat For Renewal 1947–1972. Kingsport, Tennessee: C. Davis, 1986.

- The Charlotte Observer. “The Church Must Heal, Not Flee Race Woes, Says Dr. King.” August 22, 1965. https://charlotteobserver.newspapers.com/newspage/620329672/.

- Smith, Anne Chesky. “WNC History: Martin Luther King Jr.'S Trips to Black Mountain, Montreat.” The Asheville Citizen-Times, August 14, 2022. https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2022/08/14/wnc-history-martin-luther-king-jr-trips-black-mountain-montreat/10281114002.

Additional Resources

- Video Interview with Andy Andrews

- Recording of Martin Luther King Jr. speaking in Anderson Auditorium

- Interviews with people who attended the Christian Action Conference in Montreat

- MLK speach at the Christian Action Conference (Part 1 of 4)

- Calder, Thomas. “Tuesday History: Martin Luther King’s Historic Montreat Speech, Part I.” Mountain Xpress, January 16, 2017. https://mountainx.com/news/tuesday-history-martin-luther-kings-historic-montreat-college-speech-part-i/.

- Hughs, Ina. “When Martin Luther King Came to Montreat.” Black Mountain News, June 17, 2015. https://www.blackmountainnews.com/story/news/local/2015/06/17/martin-luther-king-came-montreat/28867923/.

- North Carolina African American Heritage Commission. “Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. At Montreat (1965) | NC AAHC.” Accessed January 12, 2024. https://aahc.nc.gov/programs/nc-civil-rights-trail/nc-civil-rights-virtual-trail/rev-dr-martin-luther-king-jr-montreat-1965.

- Presbyterian Historical Society. “Martin Luther King Jr. Page 2,” April 15, 2014. https://www.history.pcusa.org/history-online/exhibits/martin-luther-king-jr-page-2.

- Service, Presbyterian News. “Montreat Conference Center Celebrates Martin Luther King’s Historic 1965 Visit.” The Presbyterian Outlook, June 10, 2015. https://pres-outlook.org/2015/06/montreat-conference-center-celebrates-martin-luther-kings-historic-1965-visit/.

- Smith, Anne Chesky. “WNC History: Martin Luther King Jr.'S Trips to Black Mountain, Montreat.” The Asheville Citizen Times, August 14, 2022. https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2022/08/14/wnc-history-martin-luther-king-jr-trips-black-mountain-montreat/10281114002/.